A few thoughts on political journalism

"You need a lot of context to seriously consider anything"

In January 2023, as part of a larger editorial and corporate exercise, the BBC released an independent “thematic review” of the “impartiality” of its coverage of “taxation, public spending, government borrowing and debt.” If you’re interested in thinking about how journalism should cover public policy and political debate, the 49-page report is very much worth reading — even if, like me, you haven’t watched, listened to or read much of the BBC’s coverage of such things.

The headline takeaway was that the review did not find systemic bias in the BBC’s coverage of economics. That’s good. But it’s not really the most interesting thing about the report.

“Impartiality” is a worthy concern, but the report works just as well as a study of whether the BBC’s coverage of such important public issues is thorough as it should be — whether such issues are being covered with the nuance, context, depth, breadth and thoughtfulness they deserve.

Whatever one’s view about any of the questions that are regularly debated about government taxation, spending, borrowing and debt, it might be agreed that they are important questions with real consequences and real stakes for real people. And so, in addition to thinking about impartiality, it’s important to ask whether such issues are receiving the sort of coverage they demand.

As Augustus Haynes, one of the great editors in the history of American journalism, once said, “you need a lot of context to seriously examine anything.”

That point is made more explicit in another review the BBC released last month, this one about coverage of immigration. Again, the review did not find consistent bias. Again, that’s really not the most interesting part.

“The most common problem this review identified was that the BBC often tells migration stories through a narrow political lens, reporting what high-profile people are saying without really getting under the skin of the issue,” Madeleine Sumption writes. “Audience research participants showed a strong appetite for more depth.”

That would include, the report later notes, the voices of migrants and asylum seekers themselves.

Across the migration report’s 75 pages, the word “context” appears 42 times. “Nuance” appears 12 times and “depth” appears 32 times.

The two experts leading the first review — Michael Blastland and Andrew Dilnot — found that the BBC’s coverage of taxation, spending and debt was generally good. But too often, they write, certain ideas — that debt is bad, that public spending is good, that tax cuts are good, that spending cuts are necessary, etc — were taken as given. Trade-offs — and there are always trade-offs whenever public policy choices are made — went unmentioned. Perspectives weren’t included. Uncertainty was not acknowledged. And they saw the BBC, like other outlets, giving into the “temptation to hype” — “breathless stories or headlines that seem to chase excitement by slanting data or evidence.”

They also were “disturbed by how many people said they didn’t understand the coverage.”

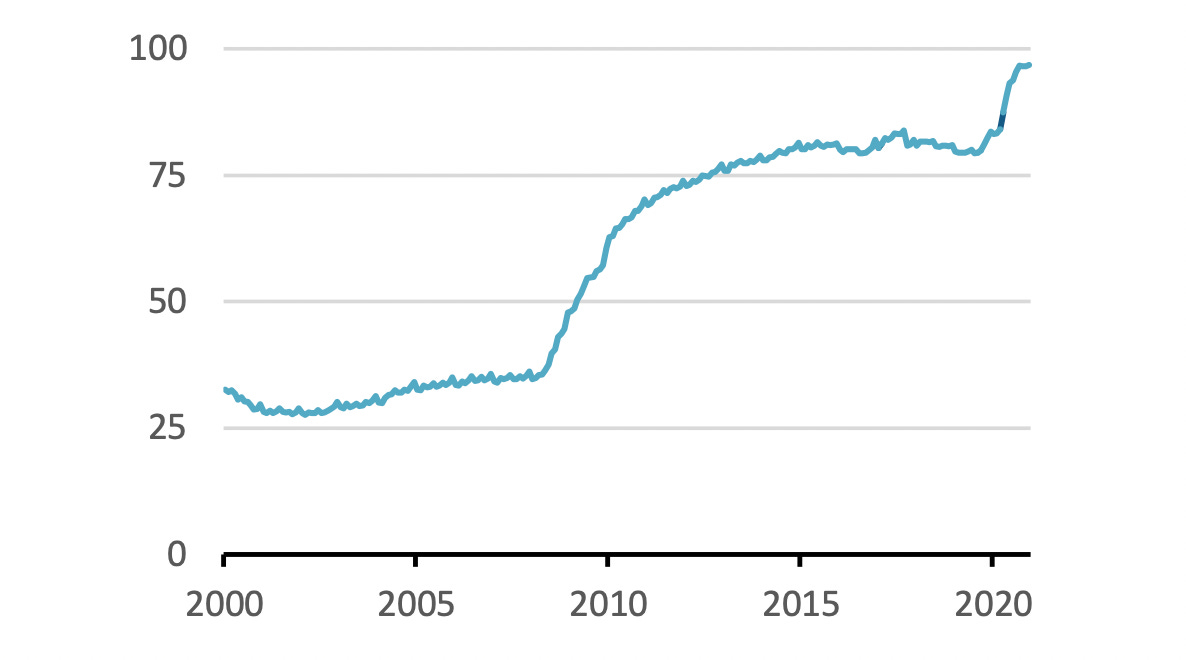

One of Blastland and Dilnot’s main points involves this graph.

As the authors note, the framing of this chart suggests there’s something readers should be concerned about here. But is there?

Maybe. But to answer that question you could realistically ask a bunch of other questions: about current and historic debt levels, about differing views on how to judge debt, and whether or how that debt should frame future policy choices.

Blastland and Dilnot spend about a thousand words thinking through this graph, the assumptions that might be underlie it, the presentation, and some of the different ways one could think about what it shows.

“The simple point is that there’s expert debate about the safe or sensible level of national debt, and how worrying it now is,” they write.

And bear in mind, they add, “that the seriousness of public debt has been a central political issue since the 2010 General Election.”

Blastland and Dilnot then make two graphs of their own. The first covers the same time period, but shows public sector debt as a percentage of GDP — the national debt as measured against the national income.

Sticking with debt-to-GDP, they then extend the timeline by 80 years to create a third graph (the orange line indicates the period covered by the first chart).

This is a useful exercise, I think, both in terms of framing and in terms of getting at what political journalism should do. Suffice it to say, I’d be inclined to use the third graph — not because it somehow disproves the first graph, but because it offers the sort of perspective that can lead to a better debate about debt.

As the BBC set out to measure its impartiality, the authors focus on how different presentations of the facts can implicitly convey a “view.” Similarly, they point with concern to phrases like “eye-watering” or “record” (at least when the actual achievement of a record is debatable).

But the authors don’t conclude that the root of the problem is “bias.” Instead, they blame “insufficient awareness of the choices and debates here.”

“Bluntly,” they write, “debt is controversial.”

And journalists need to know that — and feel comfortable and confident enough to relay it.

“Let’s hammer the point: this does not mean we advocate going the other way and saying debt doesn’t matter, or that a government has carte blanche,” they write.“[C]hoices usually entail risks on all sides. We’re saying there’s serious argument, no more. To be impartial, journalists need to understand this.”

You can take that a step further, I think, and say that, for the sake of building a strong smart and healthy democracy, political journalism would help voters understand that — that if there is going to be a political debate about debt or spending or taxation, there are serious arguments, choices, trade-offs and risks that political journalism should cover and explain. For the sake of building a stronger, smarter and healthier democracy, political journalism would put those questions and facts front and centre and tackle them with nuance, context, depth and breadth.

Early in their 2023 report, Blastland and Dilnot note that “contrary to some fears, almost nothing” in their review of impartiality “is about stopping people saying things.”

“It’s overwhelmingly about saying more, more creatively,” they write.

There are lots of questions worth asking about the media industry at present — in Canada and elsewhere — not least the rather significant question of whether there is a business model capable of maintaining much of a media industry. Context, nuance and depth cost money — even more money than the opposite.

In American circles, there are big and profound questions about whether journalism is fit for purpose — whether it is doing what Americans need it to do at this particular perilous moment in the history of American democracy. Questions about the purpose and performance of political journalism are not new, of course. But in the last decade, as the American political process has seemed to teeter on the brink of ruin, those questions have taken on new urgency.

“Our media is largely not up to the task of dealing with the challenges we face,” Sherrilyn Ifill, the American civil rights lawyer, wrote recently. “In pursuit of dollars and clicks, too many outlets have abdicated the essential part they play during times of democratic crisis.”

America’s problems are not exactly Canada’s and it would be a mistake to copy-and-paste their discussion into ours. But we can still ask how Canadian political journalism should or could be better or different. If the ultimate goal is helping to build an ever-stronger, smarter and healthier democracy — and I think it should be — what should Canadian political journalism do and how should it be?

The primary task of political journalism might be said to be holding the powerful to account — “comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable” as the old saw has it. Asking questions, demanding answers, pointing out foibles and uncovering failure. If political journalism could only do one thing, it would probably be that. But obviously political journalism can — and does — do more than that.

Ideally, I think, political journalism would hold the powerful to account and relay the news of the day while consistently and thoughtfully putting front and centre the potential consequences and ramifications of political actions and words. It would try to help voters understand as much as it reports. It would consciously aim for a better, smarter debate. It would prioritize depth, breadth, context and nuance. It would understand that very real things are very much at stake and aim to help voters understand the very real things that are very much at stake.

In All the Truth is Out, his account of Gary Hart’s implosion during the American presidential election in 1988 and everything that came after in American politics and media, Matt Bai writes that after Watergate and Hart, “the cardinal objective of all political journalism had shifted, from a focus on agendas to a focus on narrow notions of character, from illuminating worldviews to exposing falsehoods.”

Canadian political journalism remains blessedly without much interest in the personal lives of politicians. If nothing else, we have that going for us.

There’s a lot to be said for exposing falsehoods. If anything, Canadian political journalism could use a lot more of the purposeful fact-checking that has become such an engrained part of the American political ecosystem — not because fact-checking can single-handedly save democracy, but because truth and fact are vital to democracy. The idea that shared facts are essential to a democracy might sound trite, but it also might be true. But despite a few scattered efforts and experiments, there is currently no Canadian equivalent to PolitiFact, the American outlet first launched in 2007.

It’s also fair to question any claim — like Bai’s here — that something used to be somehow better. In many cases, things were just bad in different ways. But I think there is much to be said for focusing on agendas and illuminating worldviews.

In a post on Time magazine’s recent coverage of what Donald Trump might do if he returns to the White House, James Fallows, the journalist and former speechwriter for Jimmy Carter, argued that the magazine’s interview with the former president succeeded because the emphasis was on asking not “how will this play?” (ie. the potential political appeal of Trump’s promises), but on “how will this work?” (ie. what would Trump do and how would he do it). The complaint that the media focuses too much on the former is not a new one. But I think Fallows and Bai are ultimately talking about the same thing.

Explanatory journalism has come a long way in the 18 years I’ve spent covering federal politics. I’m not sure it even really existed when I started. But explanation can still feel supplementary, rather than central to the mission. The context and consequences of political words and actions should be front and centre as much as possible.

The game of politics cannot be ignored. But it is also not simply a game. While it’s periodically entertaining and dramatic, it is not simply entertainment or drama. If the last seven years in Western democracy have shown us anything, it’s that. Elections have consequences. Neither progress nor democracy are to be taken for granted. There are things at stake. And if political journalism has become very comfortable discussing political considerations, strategy and tactics, it should be at least as comfortable discussing and asking about public policy and democracy.

Almost all political journalism could stand to be less fleeting. Policy trackers are popular during elections, but much of our democracy is conducted outside official campaign periods. I think the hollowing out of newsrooms is leaving provincial and municipal governments in Canada under-covered. I think political journalism that was focused on building a stronger, healthier democracy would also be less cynical and sarcastic — or at least less willing to given in to lazy cynicism and sarcasm. I don’t think political journalism needs to be humourless, but I don’t think it should be afraid to be serious.

If there is a bias that political journalism needs to grapple with it is negativity bias. Reckoning with that does not mean that political journalism needs to adopt a new bias toward “good news.” But it does mean asking whether the tendency toward bad news ultimately results in presenting a distorted view of what’s actually going on in our neighbourhoods, communities, provinces and country.

Bill Fox, who was Ottawa bureau chief for the Toronto Star and then director of communications for Brian Mulroney, likes to use the example of the emergency support programs that the federal government created and rushed out in the midst of the pandemic. Millions of people were provided with billions of dollars in support in relatively short order — and that support likely had significant positive impacts — but, in his view, the media coverage tended to focus on those people and business who had trouble getting support.

In fairness, it has probably been a long time since Canadian political journalism was more focused on public policy than it was during the first six months of the pandemic. But Fox could make the same argument about any number of other areas of coverage. The emphasis is almost invariably placed on what’s not working or how a new measure fails to meet what advocates have called for. In many cases that criticism might be warranted. And being critical is a core responsibility of political journalism — pointing out shortcomings and gaps in government programs is one of political journalism’s most valuable services. But it’s worth asking if that’s where journalism’s responsibility ends.

Consider another example. In December, the United Nations released a report that showed, among developed countries, Canada experienced one of the largest proportional drops in child poverty between 2012 and 2021. If the UN had released a report showing the opposite — that Canada had suffered one of the worst increases in child poverty — the findings likely would’ve been well covered. But this report received little attention.

There is a lot that could still be said about why child poverty is still higher in Canada than in many other countries. But there is also no doubt a lot to be said about how Canada has been able to reduce poverty so substantially. For the sake of understanding their country — for the sake of building a stronger, healthier, smarter democracy — voters would know both things. When there is reason to believe that smart policy has been implemented, political journalism needs to be able to acknowledge as much.

It’s perhaps too easy to believe that we live in uniquely challenging times. But if that’s true — and perhaps even if it isn’t — it is worth asking whether political journalism is meeting that moment. If the challenges are immense, are they being confronted with the effort they deserve.

Fox recently wrote that, “if it is to survive and reassert its place in public discourse, then the media will have to move from the ‘news’ business to the ‘truth’ business.” The truth is a tricky business. But I think there’s something to be said for the dichotomy Fox draws and the implied differences in priorities and interests.

Amid renewed concern about the atmosphere that surrounds politics and the hostility that elected officials seem to increasingly face, someone in one of my social media feeds recently resurfaced a piece about why more women don’t run for office. The author, Kate Graham, has run three times (and lost all three times).

“Nothing affects more people than politics,” Graham wrote, pointing to that as the only (somewhat) rational reason why anyone would put their name on a ballot.

That’s also the most rational reason to write or report or talk about politics. You’re certainly not doing it for the glamour, the fashion or the supportive comments on social media. When I wrote about music, I got free concert tickets. When I wrote about sports, I got to go to baseball games. Writing about politics, I get to attend question period.

The ultimate truth of politics is that it matters — in ways a great many other things don’t. And it deserves and demands to be covered as such — with depth and context and creativity and facts and with an understanding that there are consequences and stakes.

Congratulations on this excellent article.

Gus! He was good